Site Specific Performance Final Blog Post

Framing Statement

High bridge, which was our location for our site specific performance, is the oldest bridge in the country. As the name of our piece High Bridge Histories suggests we were interested in focusing on the history of our site. It was not the literal history of the place that we were interested in but rather the relational history and social potential of the site because of the seating and café which are now present in the space. The aim of this assessment is to analyse the methodologies used throughout the process of creating our site specific performance. The main goal of the piece was to provide an audience with an aural history of high bridge and represent the transformation of the site from a non-place to a place through the performativity of everyday life conversations and interactions. Our main influence in doing this was Marc Augé and his notions surrounding places and non-places. Augé defines a place as ‘relational, historical and concerned with identity’ (Auge, 1995, 77). Using this concept and the methodologies of Georges Perec, we focused on the relational history of the high street and created a soundscape to create a piece which combined the interactions of the past with those of the performance day. Whilst Perec and Augé were the foundations of our piece we also took influence from other practitioners to establish and evolve our ideas into the final performance piece. These practitioners included: Cathy Turner’s ideas concerning palimpsest and layering, the concept of narration in John Smith’s video piece A girl chewing gum, Sue Palmer’s additions to the idea of space and non-space and Erving Goffman’s notions of performative everyday life. All of these will be analysed in more depth throughout this assessment.

After three months of research and development our performance took place at 12pm on Thursday 5th May 2016. The soundtrack was played through portable speakers that were connected to our phones/I pods. Having four speakers playing different parts of the soundtrack created the effect that the audience would only hear glimpses of the conversations attempting to emulate the real life atmosphere of the high street. Each person would enter roughly 90 seconds after the previous person, creating a staggered effect to the piece and making it visually interesting to watch as an audience member. Conversations were played through these speakers into the space, along with the dates on which the conversations were originally documented in the space. These dates were written on the floor, merging the layers of past and present, before we began narrating what was happening around us. Certain sound effects had actions that accompanied them for example when laughter was heard through the speakers we would leave the space and then enter it again whilst keeping straight, neutral faces.

This continues in the same manner until the end of the track at which point the track loops and we exit the space. The reason the track loops was to show that life doesn’t stop, our everyday lives continue on repeat again and again, us walking through the space with the track repeatedly playing was supposed to be representative of this. Whilst it was important for the piece to relate to the site, it was also important to relate it to the audience. We did this via a business card which we handed to them with a brief description of the piece, a line from the soundtrack and a link to the blog in case the audience member wanted to research into our piece further. In this way we were able to provide an insight to the audience without spoon feeding them what exactly we were trying to achieve.

Analysis of Process

After being introduced to the field of Site Specific performance, I began to consider how I could incorporate Lincoln and its history into a performance which engages with both the audience and Site in a contemporary setting. Mike Pearson and his book Site Specific Performance (2010) quickly became the main point of reference when it came to researching site specific theories in relation to our piece. We were also introduced to Cathy Turner and her theory of layering and palimpsest and it influenced our piece greatly. The layers of binaries including past/present, sound/visual and verbal/physical were all cornerstones of our piece. One element of palimpsest is the addition or removal of layers whilst still being able to see the original layer. Cathy Turner in her article, Palimpsest or Potential Space? Finding a Vocabulary for Site-Specific Performance (2004) she states that ‘practitioners have similarly come to view space as a layered entity’ (Turner, 2004, 373) re-emphasising her views on space and how it is created of many layers which we as performers implanted in various ways. We implemented this concept into our piece by writing the various dates (both past and present) on the floor in chalk, we then added a thin layer of breadcrumbs on top of the chalk dates, whilst leaving the initial layer visible. When the Pigeons inevitably came and ate the bread that was equivalent of erasing a layer making the previous layer completely visible again. We rehearsed different means of erasing the footsteps which we marked on the pavement including instantly erasing them and leaving them to the end to erase, playing with the idea of life lasting a fleeting moment and the idea of leaving literal remnants in the space.

Initially we were interested in looking at the architectural history of Lincoln due to the fact that when we were exploring the high street something that we noticed was the ornate architecture of the buildings which are now corporate shops such as Fat face and Jack Wills. After spending time contemplating the idea of architecture and its history, our interests developed to incorporate a specific site and the personal history people share with it. This notion of personal history remained with the piece throughout its conception and development although the medium changed. I initially had the idea of a collage consisting of pictures, objects, audio etc. which could map out a person’s personal history of a place thus making the spectator view said space in a way in which they haven’t before.

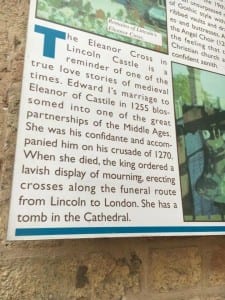

The introduction of practitioner Mark Augé and place and non-place changed our thinking towards site specific and our site in particular. His ideas state that a place is somewhere where social interactions take place, where people are human, whereas a non-place is a transient space, which is a ‘frequented place, an intersection of bodies’ (Auge, 1995, 79) where people only ever pass through on their way to somewhere significant. Throughout our devising process we viewed the high street as the transient non-place through which people pass to get to the various shops and the high bridge (the seated area in particular) as the ‘place’ where people go to socialise and interact with each other. As Walter Brueggemann states in Site Specific Performance, ‘place is a space in which vows have been exchanged, promises have been made and demands have been issued’ (Brueggemann, 1989, 26). In other words, the seated area has social potential which only becomes activated by the people who socialise within that space, a statement which is clarified by Sue Palmer who states that ‘it’s not just about a place, but the people who normally inhabit and use that place. For it wouldn’t exist without them’ (Pearson, 2010, 8). The transformation of High Bridge from a non-space to a space happens when we literally activate it by entering the space with our recorded conversations playing through the speakers.

Our initial main performance idea was in the shape of a map which was going to be hand drawn onto a whiteboard and wheeled up and down the high street. On top of this map there was going to be two layers of acetate each containing writing in different colours creating a literal palimpsest as well as a metaphorical one. The idea of palimpsest and layers was of constant interest and featured in all of our performance ideas. The metaphorical palimpsest was the layering of people’s thoughts and emotions of Lincoln to portray the multi-dimensional community which Lincoln is made up of.

Our relationship to the audience in our piece is informed by practitioner Miwon Kwon who, in her book one place after another (2002), states that ‘an artist cannot accurately represent a community and, in attempting to do so, ultimately represents himself and his own work’ (Kwon, 2002). In our original idea this community engagement came from the audience writing their perception of Lincoln as a place to live. This concept stayed within our thinking and is prevalent in our final piece as it challenges the notion that an artist cannot represent a community due to the fact that, in our piece, it is the communities’ voice which provides one of the core elements for the performance.

After discussing the potential of the whiteboard idea as an installation idea with the acetate changing every hour showing the change of activity in the high street throughout the day. I quickly became concerned about the shallowness of our piece. It looked more like a piece which was marketing Lincoln for a travel brochure and had lost any potential of the space transcending meaning for the audience. After much deliberation I came up with a new concept focusing on the primary purpose for high bridge which is conversation/communication. After discussing the theme of communication with the rest of the group, we created an idea which involved playing a recorded conversation and miming over the top of it. This brought up the question of authenticity and ownership and whether someone else’s words become mine if I speak them and whether the words lost their original meaning if repeated out of context. We attempted to introduce palimpsest by documenting people’s conversations using the methodology of Georges Perec in his work an attempt at exhausting a place in Paris (1982). We found that we only caught snippets of conversations which gave a brief glimpse into people’s lives ranging from the random and chatty to deep and meaningful conversations. The resulting manuscript was similar to the work Craig Taylor’s book One million tiny plays about Britain (2009) in which he uses everyday conversations stitched together to create scenarios to create funny and serious mini plays. The difference from our piece to Taylor’s work is that his conversations are put together to make cohesive stories whereas we want to maintain the element of hearing random lines of conversations as would be the case in the high street in real life.

Initially the piece was about recreating a moment in life in our site and questioned ownership and authenticity. Although the theme of ‘the moment’ was still present in the final performance it became more about the repetition and monotony of everyday life as shown through the dates, repeated soundtrack and the addition of us marking our footsteps. The concept behind these steps was that by marking our footsteps in the space we are making clear the footsteps that had been before whilst marking them in the present day, once again blurring the distinctions between the past and the present. We also experimented with different sound effects and different activities to go alongside those sound effects such as childish drawings on the pavement and putting dummies in our mouths.

To blur the lines between past and present further and also create a thicker textured sound we originally planned to speak the lines along with the soundtrack. This however looked scrappy when we experimented with it in the space so we therefore looked back on previous practitioners and came across John Smith and his work Girl Chewing gum (1976) who we became aware of early on in the devising process. Within his piece, Smith narrates a recorded piece of footage in an almost director like way as though conducting the world around him. In a similar fashion to Smith we overlaid the recorded conversations with us narrating the world around us, not just the people but the animals too. The difference between our piece and Smith’s is that his narration was retrospective on a recorded piece of footage whereas ours was live creating a live layer on top of the recorded one.

Performance Evaluation

On performance day, there was a stubborn busker in the space, meaning that we were unable to rehearse the piece in the space under performance conditions. Because of this there were a number of small things that went wrong which would normally have happened in a rehearsal period such as the chalk snapping and the phone falling out of my pocket. On reflection one thing we particularly struggled with was the notion of character and acting. In his book Presentation of Self in Everyday Life Goffman states that

‘When two teams present themselves to each other for purposes of interaction, the members of each team tend… to stay in character’ (Goffman, 1959, 166).

This was something that we were cautious of throughout the rehearsal process, this however became an issue because of what Goffman states above. When a captive audience of twenty plus people were placed in front of us, the natural ‘character’ that Goffman speaks of came to the surface.

Conceptually the piece was strong, with audience members saying that they heard snippets of the conversations, as was the intention, but the general aesthetic of the performance was not as striking as it could have been with better execution. Members of audience did however come up to us after the performance and say that they would never see the space in the same way again because of our performance which was one of the intentions of the performance (to make the audience view a space in a different light that before) and we successfully gave them the means to go away and look up the project if they wanted to in the form of a business card with the blog address on. If we were able to perform the piece again I would ensure that the piece was well rehearsed and slick to make for an aesthetically pleasing piece, I would also make it longer in order to make it clear to the audience what it was were attempting to portray as I felt like the moment the audience began to engage with the piece it was over.

Sight Specific Performance has broadened my preconceptions surrounding performance and has opened up numerous possibilities for performing in non-conventional venues in the future as I now feel as though I can tackle these venues, fully equipped with the knowledge and understanding necessary to create an engaging and intellectually stimulating piece.

Word Count – 2451

Bibliography

Auge, M. (1995) Non-Places introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. Verso: London.

Brueggemann, W. (1989) ‘The land’, in Lilburne, G. (ed.) A sense of Place: Christian Theology of the Land. Abingdon Press: Nashville

Ewwtubes (2012) John Smith – The Girl Chewing Gum 1976. Available from https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=a+girl+chewing+gum [Accessed on 3 March 2016]

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Penguin: London.

Kwon, M. (2002) One place after another, Site specifc art and locational identity. MIT Press: Massachusetts.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site- Specific Performance. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke

Taylor, C. (2009) One million tiny plays about Britain. A and C Black: London.

Turner, C. (2004) Palimpsest or Potential Space? Finding a Vocabulary for Site-Specific Performance. New Theatre Quarterly, 20(4, November) 373-390.