— IN-BETWEEN —

HERE ——– YOU ——– THERE

FRAMING IT

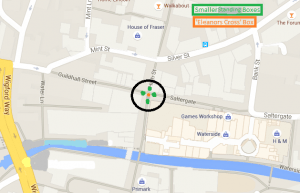

In-between, performed 12am-4.30pm on 6th May 2016, formed out of many different conceptual ideas that, through extended development and experimentation, became a minimalist, gallery-esque piece, which put the observer between different mediums, moments and emotions. While the piece took place in a ‘shop to let’ within the Waterside Shopping Centre on Lincoln High Street, it twisted the expectations and perceptions of what a shop should be; blurring the lines of normality and identity. We wanted to give something back to the public, breaking the cycle of consumerism that runs day by day, 9-5, giving them a chance to stop and take some time to relax.

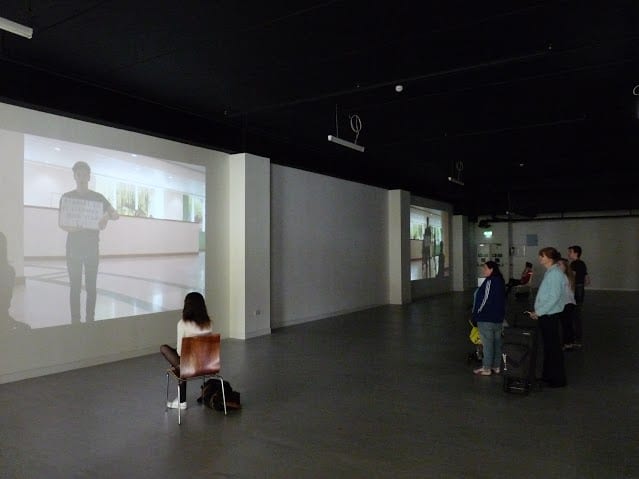

Given that our site was situated in-between H&M and Roman, we felt it was even more important to reflect the breaking of a cycle as by simply using the space for something other than a shop we in turn created a visual representation of that very break in the cycle. As people walked past the shop windows they inadvertently become part of the piece as there was a monitor connected to a camera filming the walkway in each shop window (fig.1), this camera feed was also projected into the space with a chair in front of each projection (fig.2). Stood in-between the cameras and the shopping centre walkway were two of us, still, waiting; waiting for someone to have a personal and intimate moment with. Once two people had occupied the chairs we then began the same, one-sided conversation that went page by page (fig.3), the third one of us controlled the shop floor and acted as an usher. Once the conversation had come to an end the two people were then invited to switch seats and have another conversation. Following the minimalist aesthetics of the piece we incorporated that into our writing by having the same conversation but with a simple additive of the conjunctions, ‘also’ and ‘too’. The two conversations finish, the people get on with their day and the two of us are left standing with a page saying, ‘Waiting’.

Paradoxically waiting for the cycle to begin again and for the other to stop.

Throughout the process we looked into many different artists and performances and originally drew influences from artists like Adrian Howells and his intimate transactions.As the piece developed it became more influenced by artist like Dan Graham and Vito Acconci, who worked with the architecture of sites and both created minimalist work that connected with people on a personal level. We didn’t take a direct artistic influence from practitioners but more their methodologies and way of approaching concepts. The notion of intimacy still ran through to the end result and we took a heavy influence from Michael Pinchbeck’s piece, Sit with me for a moment and remember. A piece where a moment was made significant through poetic language and the medium sound.

PROCESSING IT

I’ve always been an observer, I like to take in my surroundings so on our first exploration of Lincoln High Street, which was our chosen site for the performance, it was incredible to see how much I had missed. The architecture and layout was stand out – every exposed beam, broken slate, gargoyle, back passage, wall, closed door started become the present face of a forgotten story. The multiple layers, or palimpsest, was something that stayed with us for a long time throughout the process, we continued to put meanings behind various ideas, leading to a conceptual view point for many of them. This later proved to be our down fall, where we were left with an overlapping and blurring of concepts; I will touch on this later, however.

Wondering around the streets of Lincoln we came across many areas where we would find ourselves simply looking, thinking.

Walking up and down and looking high and low along the High Street quickly started to show how any slight abnormality surrounding the site is noticeably picked up on by the public. Eyes would begin to watch and start to question what you’re doing. This brought to our attention the importance of the public interaction with the site, especially the High Street, which is almost always inhabited by people. We wanted to disrupt this flow, or more considering this analogy:-

If you drop a rock into a river the ripples will eventually became part of the flow, as too will the very rock that created them.

Fleeting moments are always there but only beautiful if you catch them.

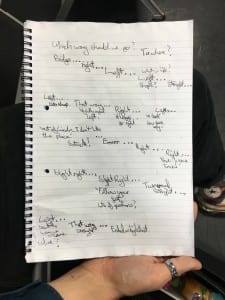

The social interaction became a focal point for our early practical research and experiments. Elliot, Laura and I kitted up with a note pad, pen and the question, ‘Which way should we go?’ and targeted the Lincoln public. We wanted to see how the public would react to something without context, to test preconceptions and how interactive and willing people would be. Here is a record of our experience:

The array of responses was the most intriguing thing, with ‘What, in life?’, ‘Out of Lincoln, I don’t like the place.’ and ‘Follow your feet.’ Were some of the most significant responses we had, thanks to the absence of context or knowledge. Slighting mixing the mutual understanding of a question opened up the prospect of something new and abnormal, which we grew instantly attached to. While carrying out this experiment it’s also important to note that the simple action of approaching someone with a note pad and pen played into the norm and preconception of a High Street, they are most likely there for you information, money or 5 minutes of your time. People diverted there course and some simple ignored us and implied they weren’t interested.

Considering the idea of place and non-place, the High Street fits into the realm of non-place, and we wanted to continue this through-line within our piece and throughout our research and practical experiments. With this is mind we decided to engage with the site in a way that was semi-permanent and give a section of the high street meaning and a sense of purpose, instead of a transitional street between places. We also want to create a piece that was “Generated through trial and error, through improvisation and the testing of proposals over a protracted period” (Pearson, 2010). Pearson was fundamental to me for grasping site and we felt this notion was crucial to creating our final piece.

As seen in the video, we had a start point and drew a chalk line along a pathway that was being swept clean, we also had a sign saying, ‘Is this a test?’ and one of us recorded the whole experience. When our journey got disrupted we added a reverb to the line and if anything was said to us we wrote it along the line. When the chalk ran it, it signified the end of the journey so we left the sign at the end and walked back along our recently created pathway. Walking back it was hard to stick to the pathway and proved that anything you try to implement onto an already established order is always going to struggle to shine through.

This was also the first time we had recorded our work and it gave a whole new perspective on how we could mediate our performance. When we’re walking back along the line the video seems to radiate purpose, really dragging the watcher into the journey. The moment when the railway line barriers went down really emphasised to us the importance of spontaneity and working with your site. Catching those moments on camera verified the beauty of them and pushed this multi-media aspect of a performance to be a fundamental part to our final piece.

Furthering our exploration we decided to look into the Waterside Shopping Centre, Laura had always been keen on finding a space there as she had seen the Frequency Festival in an empty shop to let. She loved the use of space and could envisage many ideas within spaces like that, and to our luck there was a newly refurbished, empty shop up for let. We straight away inquired about using it for our piece, leasing with the shopping centre manager and administrator. We discussed the terms and they agreed to us using it, though, there was always the chance of the shop being let out before our performance date. This didn’t stop us from diving straight into the site and to start thinking of potential ideas. We had our site confirmed and the creative focus was aimed there, but we did for the time being, have other sites on the back burner.

We first of all loved the openness and creative control we had over the space, it was a blank canvas ready for lines to be drawn. The two shop windows at the front of the shop instantly caught our attention, we pretty much saw them as two different performance spaces – the glass giving them their own viewing screen. We also saw the windows as an opportunity to be able to stream a recording of outside the shop, inside; we felt this was essential as we wanted to pursue concepts of surveillance. Continuing that focus we quickly wanted to test out live streaming within the space, so we set up Facebook Live and streamed a short piece titled, Any Requests?, to the public of the social media site.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Z_ZjEAzWtM&feature=youtu.be

After spending multiple sessions in the space and talking over initial thoughts and experiments we formed fairly conclusive idea that was based around becoming a shop, fitting in with the site of the shopping centre, and posing questions about surveillance, archives of personal information, consumerism and the general consensuses of what is ‘free’?

We thought of selling photos of CCTV cameras, barbed wire, closed off doorways etc., but they would all have the price tag of ‘free’. This was to play on the perceptions of freedom and what it means to be free if we are restricted by these system put in place. We would only ask for bit of personal information in return for a photo, this would then be stored in the archive at the back, which would store lots of other info; drawing from Howells site work and transactions. Another layer of surveillance was the camera and monitor in one shop window, which was then streamed into the archive, where people could have observed and reported any abnormal behaviour. We also incorporated an attack on consumerism in the other window, with a continual ingestion of liquid from hose pipe – a reflection of society and how we over consume.

We presented our ideas to Stephen Fossey and Conan Lawrence, our module tutors, and talking through it with them uncovered conceptual confusions and too many overlaps of ideas, as is talking about it now. We had got lost and tried to produce too much. What stood out for them, however, was the use of cameras and monitors, bringing the outside into the space, and the concept of breaking the cycle of consumerism. We got thinking and looked back at previous experiments.

While visiting Amsterdam during the process I went to De Appel, a contemporary art gallery that was hosting work by Saskia Noor Van Imhoff and Alicja Kwade. Van Imhoff produced a site specific installation piece that showed the gallery deconstructed, putting forward questions about the value we put to objects and the layers behind everything we see. (De Apple, 2016)

The minimalist design of the piece and the focus on architecture made me rethink how we could use the architecture of our site. Could also see similarities within the gallery aesthetics of our site.

We began to see a natural mirroring within the space, the pillars provided gaps that could represent the shop windows (fig.4). Working on our feedback we formulated a transformed piece that was heavily cut back and focused on the use of cameras and projections and giving something back to the public, in-between their routine that runs through the High Street and shopping centre. We wanted to use intimacy/affection as a form of giving so started working on a script that we could show the audience, through a series of pages of simplistic, beautiful and thought provoking language. We looked into the work of Dan Graham and Vito Acconci and could see their artistic use of minimalism and architecture and this helped us reinforce our ideas. Our piece, In-between, was essential there but we had no idea what the result would be till we got into the space, with all the technical gear, on the morning of the performance.

REFLECTING ON IT

The performance finished and we closed up shop along with the rest of the shopping centre, leaving the space as it begun. Empty, nothing. All that remains is the memory, a fleeting moment that was only caught by a few. The few that did, left the space and got on with their day feeling something, and it wasn’t all the same as the piece produced an array of individual experiences. Depending on whether you sat on the chairs or eavesdropped on the conversations from an outside perspective was the variable that produced a variety of emotions.

The people observing seemed to empathise with the ones who were having the conversation, feeling sadness as they were able to fully sense the distance and separation between the person sat and the one in the projection. I, as a performer could also feel a longing and sadness, almost turning to desperation as I knew every moment was coming to an end. This, however, didn’t hamper the lasting connection made with individuals.

As an individual sat in a chair that was their moment, a moment to take a break and feel. We were pushing the boundaries of intimacy and what it actually means to connect with someone, and if people even could. As the performance begun a paradox was instantaneously created as the two people sat in the chairs were thrown into an in-between world of projections and shadows, closeness and distance, intimacy and the lack of. Posing the question of whether the conversation was even real or not, yet simultaneously cementing that moment and what they felt to be the very essence of something real.

(The shadow of the person puts them within the projection, making them feel close to the performer, yet at the same time is the very definition of the absence of something. Being in this in-between world leaves the audience unable to fully grasp reality and instead leaves them questioning it.)

The shadows worked particularly well as it enabled a physically visual connection to be created between performer and audience. Not only did it place the audience within the scene but it also, upon reflection, posed the possibility of working with the shadows more. With attempts of interaction between the projections and shadows and the use of objects to create more of a scenario or maybe this pushes too far away from the simplicity and makes the in-between world too explicit.

.

The complication of the mannequin display in one of the shop windows actually ended up being quite positive, they added a normality to the space, which otherwise would have been completely separate from the Waterside Shopping Centre. Looking back now it would be very interesting to see the parameters and outcomes of this performance if it were situated within a working shop. The minimalism and focus on the two individuals would disappear, though the eavesdropping aspect enters new possibilities and opens up the chance to play with moralities and ideas of connection in such an active, public space. The normality continued through the natural creation of a sound-scape; the constant hum of the Waterside Shopping Centre ran throughout the piece and as Serra says, ‘to move the work is to destroy the work.'(Serra, 1994), we really felt we had created a piece of art that couldn’t have been created anywhere else.

Not only has this process been a journey of discovery through Lincoln and its people but also the world of Site Specific Performance. This area of performance gives you the opportunity to actively engage with the world around you, interacting with people on a personal and real level. Understanding the paradigms of Site Specificity and what it means has made me see any place, space or non-place as an opportunity, a story or a moment. Theatre is not only about producing a spectacle, the entertainment suggests a distance from self, it is also about blurring the boundaries and lines of the everyday, to question and to imply a reflection of self.

Word count: 2,743

Bibliography:

Pearson, M. (2010). Site-specific performance. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Potente, L. (2016). live. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Z_ZjEAzWtM&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 13 May 2016].

Potente, L. (2016) In between. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMsIieFvDFc&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 13 May 2016]

Sargent, E. (2016). Site Specific: Chalk expriment. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8B4XnAQjjc&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 13 May 2016].

De Appel.(2016) Available at: http://deappel.nl/visit/programme/activity/?id=1015 [Accessed 10 May 2016]